海外之声 | IMF副总裁:地缘政治如何重塑全球贸易与货币体系

导读

近年来,新冠疫情和地缘冲突等多重冲击使全球经济格局发生了深刻变化,地缘政治力量对国际贸易流向和金融体系的影响愈发显著。基于经济安全与国家利益的考量, 各国正在重新选择贸易伙伴并调整国际投资方向。与此同时,部分国家对美元在全球交易与储备中的主导地位提出质疑,并积极探索货币多元化路径。

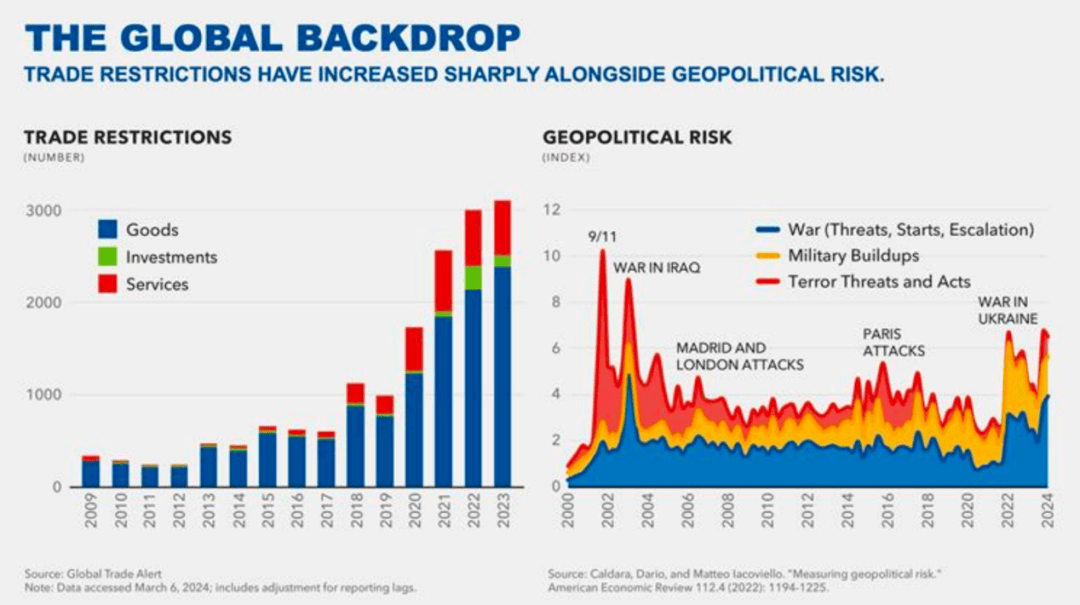

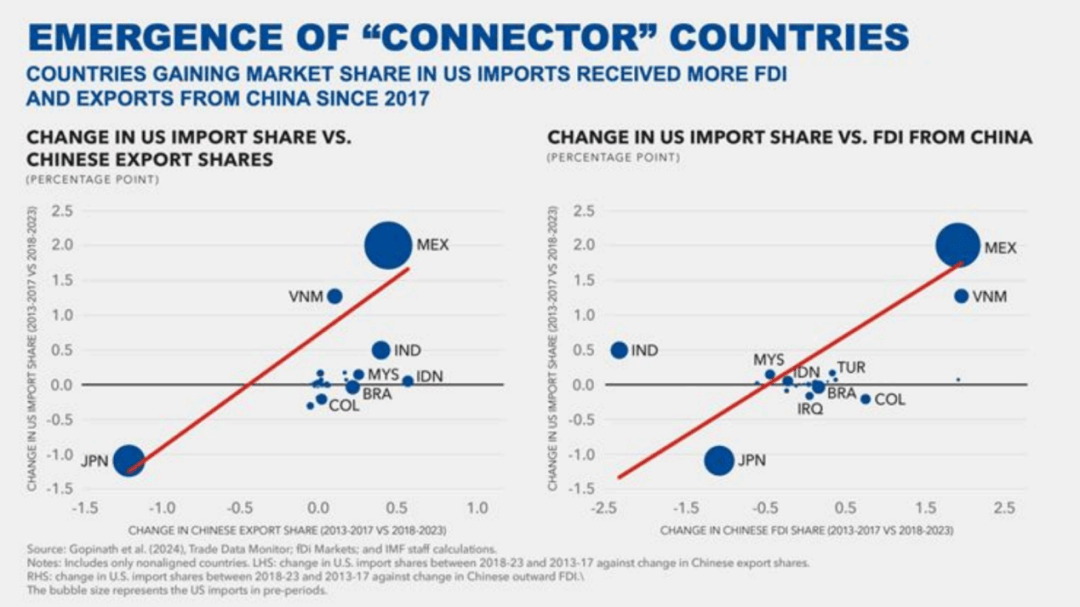

自2019年以来,全球新增贸易限制数量激增。第三方国家,如墨西哥和越南,作为贸易中转站的作用愈加突出,部分缓解了贸易限制的经济影响。这一现象揭示出全球供应链的复杂性与区域化趋势的深度交织。

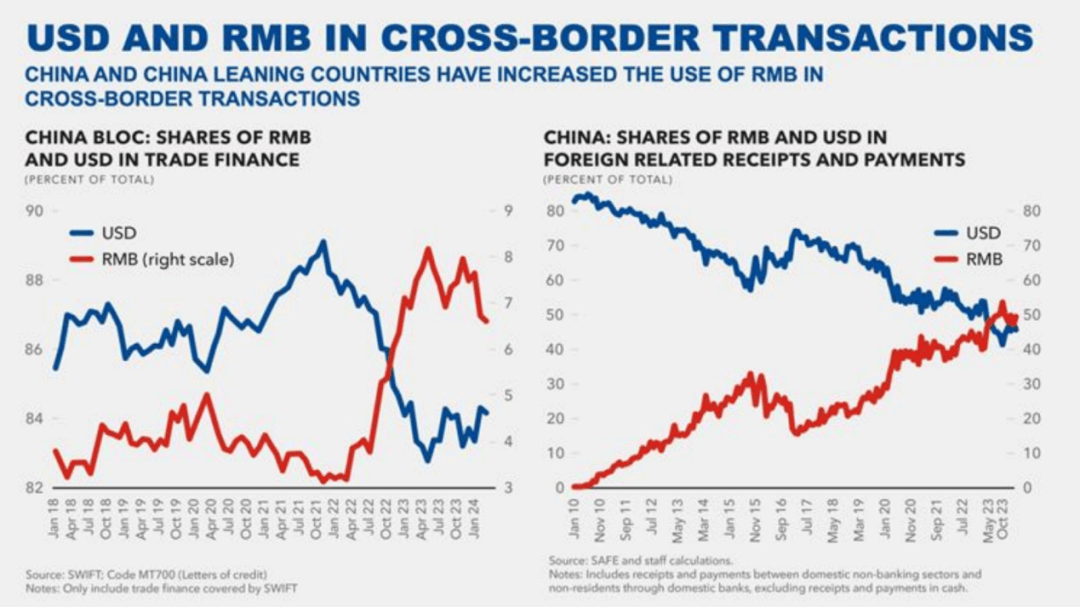

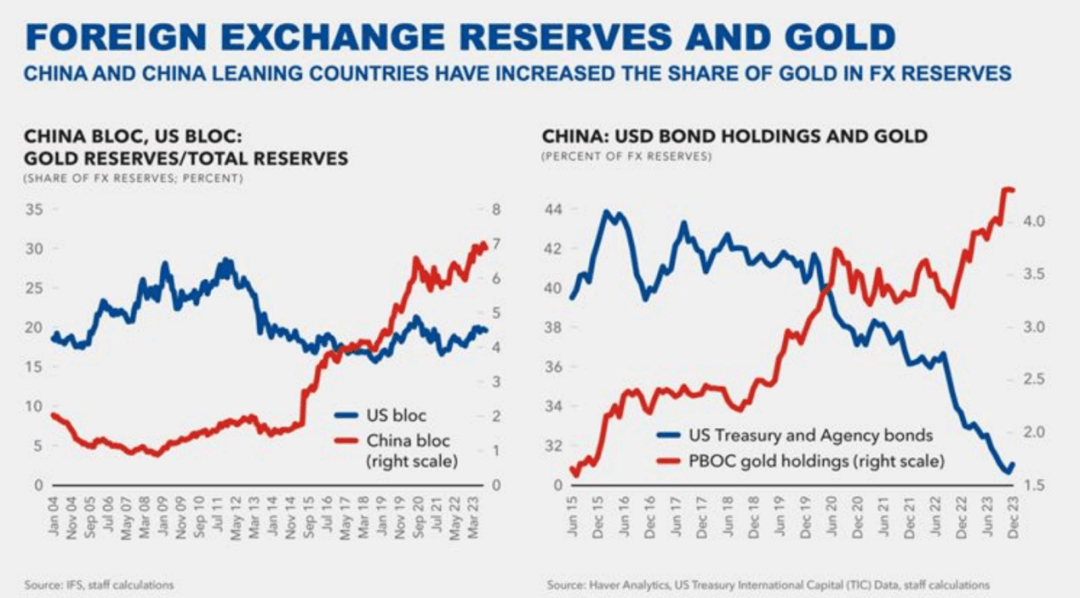

在货币领域, 尽管美元依然在全球贸易与金融交易中占据主导地位,但人民币的国际使用率(尤其在中国经济圈内)显著提升。同时,地缘政治风险促使许多国家央行增加黄金储备,以对冲制裁风险并减少对特定货币的依赖。这一变化不仅体现了国际金融体系的多样化需求,也预示了未来全球货币格局的潜在调整。

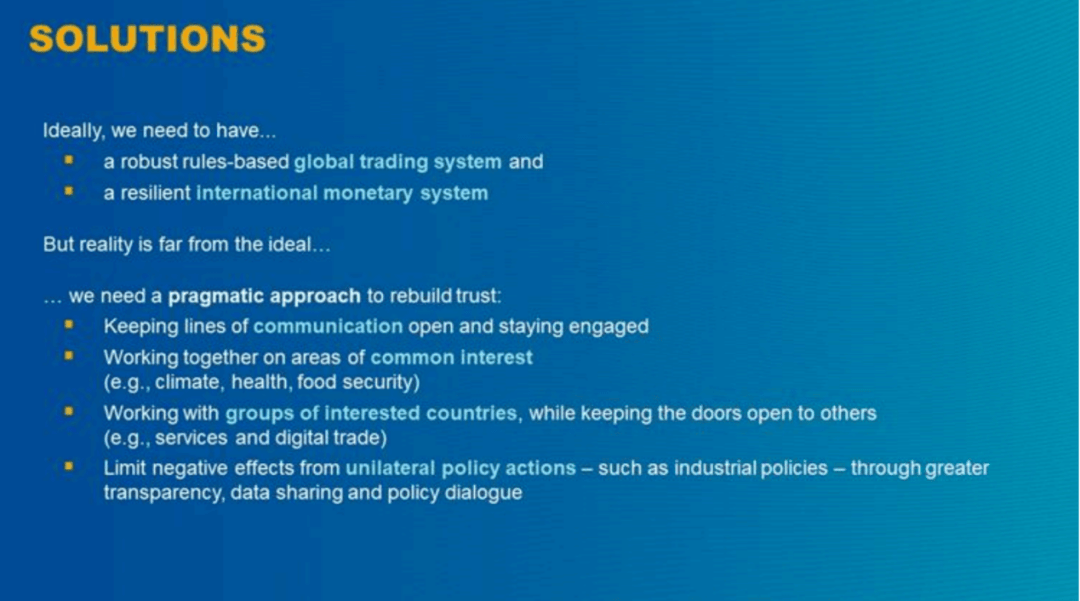

地缘政治分化带来的经济成本可能是深远的。从贸易的碎片化到资本流动的限制,这些变化将削弱全球经济效率和资源分配的优化能力,尤其对高度依赖进出口的低收入国家造成严重影响。这些国家在农业、矿产等关键商品的供应链中往往处于脆弱环节,当贸易壁垒增加时,其经济安全与社会稳定可能面临双重挑战。然而,地缘政治的分化并非不可逆转。 然而,通过恢复多边贸易体系的规则基础,增强国际间的合作与信任,各国仍有可能减轻冲突带来的负面影响。在气候变化、数字经济等领域寻找共同利益,将为减少地缘政治风险、保持经济一体化提供重要契机。

原文(节选):

Geopolitics and its Impact on Global Trade and the Dollar

First Deputy Managing Director Gita Gopinath

Series on the Future of the International Monetary System (IMS)

Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research

May 7, 2024

After years of shocks—including the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—countries are reevaluating their trading partners based on economic and national security concerns. Foreign direct investment flows are also being re-directed along geopolitical lines. Some countries are reevaluating their heavy reliance on the dollar in their international transactions and reserve holdings.

All of this is not necessarily bad. Given the recent history of events, policymakers are increasingly—and justifiably— focused on building economic resilience. But if the trend continues, we could see a broad retreat from global rules of engagement and, with it, a significant reversal of the gains from economic integration.

Despite these trends, there are not yet clear signs of deglobalization at the aggregate level. Since around the time of the global financial crisis, when the 1990s-early 2000s hyper-globalization came to an end, the ratio of goods trade to GDP has been roughly stable—fluctuating between 41 and 48 percent.

But under the surface, there are increasing signs of fragmentation. Trade and investment flows are being redirected along geopolitical lines.

For example, China’s share in U.S. imports declined by 8 percentage points between 2017 and 2023 following a flare-up in trade tensions. During the same period, the U.S. share in China’s exports dropped by about 4 percentage points.

And direct trade between Russia and the West collapsed following the invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions on Russia.

At the same time, quarterly growth in trade within blocs only saw a 2-percentage point drop.

On average in the period after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we see that trade and FDI between blocs declined by roughly 12 and 20 percent more than flows within blocs, respectively.

It is notable that these patterns are not driven uniquely by the U.S. or China and hold up even when you take these two countries out of the picture.

How bad could it get?

To gauge the potential magnitude of fragmentation along geopolitical lines, let’s compare the current trade fragmentation with that of the Cold War period.

Trade between the rival Western and Eastern blocs was significantly depressed during the Cold War, relative to trade within these blocs.

Thus far, today’s fragmentation is not significantly different from the initial years of the Cold War. However, compared to the average “between-bloc trade shortfall” during the entire Cold War period, fragmentation so far is an order of magnitude smaller.

But there is still cause for concern. Trade fragmentation is much more costly this time around because unlike the start of the Cold War when goods trade to GDP was 16 percent, now that ratio is 45 percent. Moreover, while back then countries within a bloc were taking off trade restrictions, now we are in an environment of growing protectionism with several countries turning inward.

The potential role of non-aligned countries in the current trade frictions also makes the situation today different from the Cold War experience. The evidence suggests such countries did not play an important role serving as connectors between rival blocs during the Cold War—likely because they had a much smaller economic footprint and global supply chains were not yet developed. Today, they have greater economic and diplomatic heft and are much more integrated into the global economy. Their role as connectors this time round can help attenuate some of the costs of fragmentation.

If fragmentation deepens, what would be the economic cost? And how will those costs be transmitted?

Trade is the main channel through which fragmentation could reshape the global economy. Imposing restrictions on trade would diminish the efficiency gains from specialization, limit economies of scale, and reduce competition. The capacity of trade to incentivize within-industry reallocation and generate productivity gains would be stifled. Less trade would also imply less knowledge diffusion, a key benefit of integration, which could also be reduced by fragmentation of cross-border direct investment. A useful example is Brexit. Because of the extensive interlinkages between Europe and the UK, Brexit is thought to have had a sizable negative effect on the UK economy.

There would also be costs from financial fragmentation. It would limit capital accumulation-because FDI would be reduced-and affect the allocation of capital, asset prices, and the international payment system. Financial fragmentation could also lead to weaker international risk sharing, resulting in higher macro-financial volatility for individual countries, and higher crisis risks due to idiosyncratic shocks. The global payment system could become fragmented along geopolitical lines with the emergence of new payment platforms with limited or no interoperability. This could lower efficiency, and lead to fragmented standards and regulation.

In addition, FX reserves could be re-aligned to reflect new economic links and geopolitical risks. A global system with multiple reserve currencies could have several benefits, including a larger pool of safe assets and more opportunities for FX reserve diversification. But the stability of such a system would be at risk without strong policy coordination among all reserve currency issuing countries-including through a network of swap lines. This would not be possible if the world is divided along geopolitical lines.

The estimates of the economic costs of fragmentation vary widely and are highly uncertain. In a mild scenario with low adjustment costs, losses could be as low as 0.2% of world GDP, while in an extreme trade fragmentation scenario with limited ability of economies to adjust, losses could be as high as 7 percent of global GDP As for foreign direct investment, fragmentation in a world divided into two blocs centered around the U.S. and China with some countries remaining non-aligned could result in long term losses of around 2 percent of global GDP.

(本文观点仅供了解海外研究动态,不代表平台的意见和立场。)